Tragic Flight: The 1960 Football Team Plane Crash

The news arrived on the last Saturday of October, 1960, desolating families, stunning the campus, and shocking the country. The Arctic-Pacific chartered plane carrying the Cal Poly Mustang football team had crashed and burned on takeoff at the Toledo, Ohio, airport. Earlier that day they had played nearby Bowling Green State University.

Sixteen Mustang football players, the student manager, a member of the Mustang Booster Club, and four others perished that October 29th. Of the forty-eight persons aboard the Curtiss C-46 aircraft, another twenty-two were injured, some gravely. Dense fog, later determined to be a major factor in the accident, slowed ambulances trying to reach the airport twenty miles east of Toledo.

At 3:30 a.m., Vice President Robert Kennedy and Dean Clyde Fisher began telephoning the parents and wives of those lost. “It was one of the most nightmarish, heartrending tasks I’ve ever attempted,” Kennedy later recalled. “The worst part of it was calling the parents, most of whom didn’t know there was a wreck.”

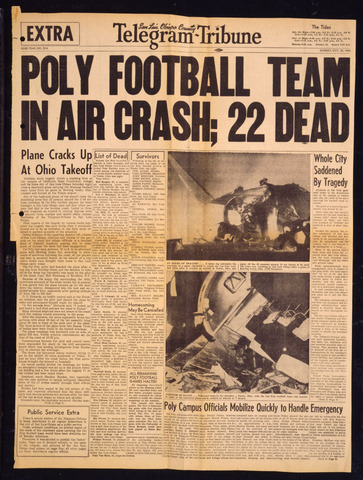

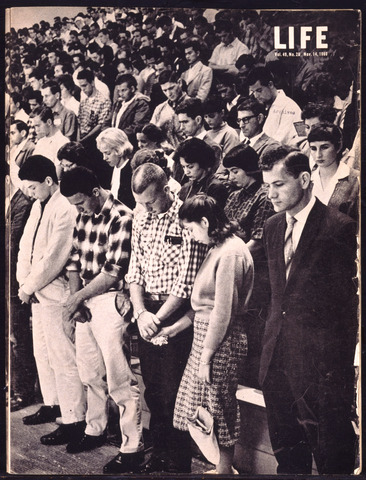

At dawn that Sunday, flags on campus and across San Luis Obispo County were lowered to half-mast. Vice President Kennedy spent the early morning hours Sunday reading wire reports at the Telegram-Tribune, whose staff was busy getting out an extra edition headlined “POLY FOOTBALL TEAM IN AIR CRASH; 22 DEAD.” Journalism students began the grim task of reporting on the loss of their classmates for the student newspaper. Two weeks later, Life magazine published an article, “Campus Overwhelmed by a Team’s Tragic Flight.”

The grief-stricken campus reluctantly began another week of classes on Monday morning, October 31. Classes were dismissed at 10 a.m. for a memorial service in Crandall gymnasium, which was filled to capacity by students, faculty and townspeople. President Julian McPhee left for Ohio to be with the injured and their family members. “I cannot praise the people of Toledo and Ohio enough,” McPhee said to a reporter. “And the alumni in that area at the time of the tragedy were truly helpful. We learned where the heart of America is — it is in the compassion of its people.”

The Red Cross played a vital role in the aftermath of the devastating accident. On the scene almost immediately, Red Cross volunteers compiled reports from three area hospitals on the condition of survivors. They conveyed personal messages from the bedsides of the injured to parents and wives at home and worked with local Red Cross chapters in students’ hometowns to assist family members. Funds for travel to Ohio, for living expenses, and other necessities were advanced or provided by the humanitarian organization.

Five women were widowed and eleven children lost a father in the accident, while several widowed mothers lost their sole support when their sons died. Many of those who survived faced daunting medical bills.

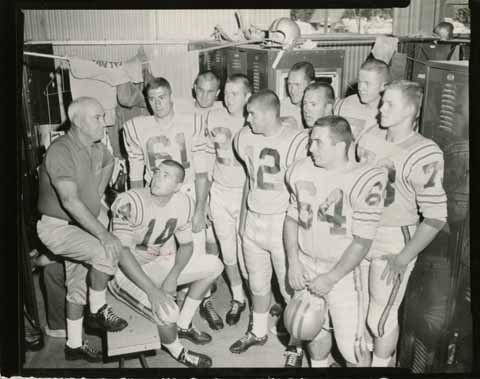

Image caption (above): The 1960 football team, in the last photo taken before the plane crash on October 29 that took 22 lives.

Image caption (below): Front page of the extra edition of the San Luis Obispo County Telegram Tribune, Sunday, October 30, 1960.

Memorials and the Mercy Bowl

In the midst of their sorrow, the campus community searched for additional ways to honor the dead, the injured, and their families. A memorial fund was quickly organized “to accept and administer charitable funds and contributions to aid survivors and the families of students killed in the airplane accident.”

In the midst of their sorrow, the campus community searched for additional ways to honor the dead, the injured, and their families. A memorial fund was quickly organized “to accept and administer charitable funds and contributions to aid survivors and the families of students killed in the airplane accident.”

Sympathetic wires, cards, and letters flooded campus mail as news of the accident was broadcast around the country. Cal Poly boosters, alumni, parents and other friends of the college sent their condolences and financial contributions to the survivors. Cal Poly Pomona staff made one of the first donations, which was matched by gifts from Bowling Green State University. Other colleges, high schools, grammar schools, service clubs, alumni organizations, and fraternal groups contributed to the fund in the months to come. Other support came from individuals throughout the country who had never heard of Cal Poly before the accident, but were moved to share their condolences and make contributions. Benefit events, many sponsored by campus clubs and generous local businesses, included football and basketball games, golf matches, rodeo events, rummage sales, concerts, dances and movie screenings. John Madden, a former tackle with the Cal Poly Mustangs during the 1957 and 1958 seasons, arranged a benefit match with the Hancock Junior College team he coached at that time. The National Football League contributed $7,500 to the fund.

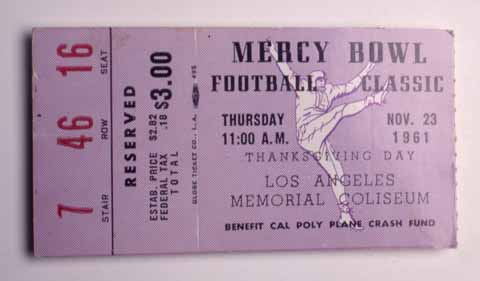

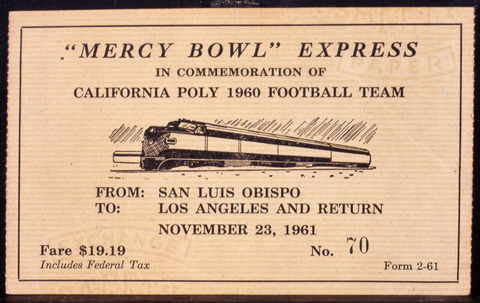

Los Angeles County Supervisor Warren Dorn, and his friend, entertainer Bob Hope, conceived the idea of a “Mercy Bowl” to add to the Memorial Fund and aid crash survivors and families. The Thanksgiving Day event was organized by Dorn and Ferron Losee, the athletic director at L.A. State. On November 23, 1961, the bowl game matched Fresno State against Bowling Green State at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. The Southern Pacific scheduled a special train to carry San Luis Obispo residents to the game. Roy Easley, captain of the L.A. State team, sent letters to captains of most of the country’s college teams, urging them to buy a symbolic eleven tickets. The one-time event attracted a crowd of 33,145 and swelled the Memorial Fund. The Memorial Fund Committee, chaired by Dean Clyde Fisher, disbursed $278,000 before it was dissolved in 1971.

Los Angeles County Supervisor Warren Dorn, and his friend, entertainer Bob Hope, conceived the idea of a “Mercy Bowl” to add to the Memorial Fund and aid crash survivors and families. The Thanksgiving Day event was organized by Dorn and Ferron Losee, the athletic director at L.A. State. On November 23, 1961, the bowl game matched Fresno State against Bowling Green State at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. The Southern Pacific scheduled a special train to carry San Luis Obispo residents to the game. Roy Easley, captain of the L.A. State team, sent letters to captains of most of the country’s college teams, urging them to buy a symbolic eleven tickets. The one-time event attracted a crowd of 33,145 and swelled the Memorial Fund. The Memorial Fund Committee, chaired by Dean Clyde Fisher, disbursed $278,000 before it was dissolved in 1971.

Image caption (above): A page from the Life magazine article, November 14, 1960.

Image caption (below): A ticket to the Mercy Bowl, a benefit for the Cal Poly Student Memorial Fund.

The 1961 season and the legacy of the crash

President McPhee, always a strong supporter of athletics, considered eliminating football in the aftermath of the crash. The 1961 season saw thirty-five players suited up, ten of whom were crash survivors. Cal Poly and other Cal State campuses restricted travel to FAA-approved commercial carriers and, for a time, authorized athletics travel only to states bordering California.

President McPhee, always a strong supporter of athletics, considered eliminating football in the aftermath of the crash. The 1961 season saw thirty-five players suited up, ten of whom were crash survivors. Cal Poly and other Cal State campuses restricted travel to FAA-approved commercial carriers and, for a time, authorized athletics travel only to states bordering California.

The 1960 Cal Poly air disaster was also the catalyst for a major shift in aviation policy. Previously pilots could not be prevented by the control tower from taking off in bad weather if they were willing to make the attempt. In the wake of the accident, the Federal Aviation Authority ordered that air traffic controllers, rather than pilots, would authorize departures. Permission to take off was denied to any commercial airline carrying passengers or property when runway visibility is less than one-quarter mile or visual range is less than 2,000 feet. Although the new order technically applied to all airlines, it now specifically included non-scheduled charter flights such as the one that had carried the Cal Poly football team.

A plaque memorializing the 1960 football team members who lost their lives rests at the foot of the flagpole in Mustang Stadium. A duplicate plaque was placed in the peristyle end of the coliseum after the 1961 Mercy Bowl game.

In July of 2000, a new plaque honoring the team’s survivors was dedicated during Cal Poly’s All-Sports Millennium Reunion. Al Maranai, a standout sophomore lineman that fateful year, made his first trip to campus in 40 years for the dedication. Maranai sustained severe leg injuries in the crash, ending his hope of a professional sports career. Memories of his fallen teammates — star receiver Curtis Hill in particular — were shared that evening with Carl Bowser and other crash survivors. An element of surprise was added to the poignant memories that evening when Bowser announced the nomination of Al Maranai and Curtis Hill to Cal Poly’s Athletic Hall of Fame, followed by induction ceremonies in October of that year.

In July of 2000, a new plaque honoring the team’s survivors was dedicated during Cal Poly’s All-Sports Millennium Reunion. Al Maranai, a standout sophomore lineman that fateful year, made his first trip to campus in 40 years for the dedication. Maranai sustained severe leg injuries in the crash, ending his hope of a professional sports career. Memories of his fallen teammates — star receiver Curtis Hill in particular — were shared that evening with Carl Bowser and other crash survivors. An element of surprise was added to the poignant memories that evening when Bowser announced the nomination of Al Maranai and Curtis Hill to Cal Poly’s Athletic Hall of Fame, followed by induction ceremonies in October of that year.

When interviewed on a recent anniversary, President Baker said the crash “was certainly a tragic event for the university. And it’s a part of the history of the university. It’s important to remember them.”

Image caption (above): Surviving team members with football coach Roy Hughes.

Image caption (below): Special round-trip ticket to the Mercy Bowl benefit game.

In Memoriam

- Larry Austin, 23, Physical Education sophomore

- Rod Baughn, 21, Mechanical Engineering junior

- John Bell, 26, Physical Education sophomore

- Dean Carlson, 20, Mechanical Engineering sophomore

- Joel Copeland, 23, Physical Education junior

- Victor Hall, 23, Social Science junior

- Guy Hennigan, 20, Physical Education junior

- Curtis Hill, 21, Physical Education senior

- Marshall Kulju, 20, Aeronautical Engineering junior

- Jim Ledbetter, 19, Aeronautical Engineering sophomore

- Lynn Lobaugh, 20, Social Science junior

- Wendell Miner, 21, Journalism sophomore and team manager

- Don O’Meara, 25, Physical Education junior

- Ray Porras, 27, Physical Education senior

- Wayne Sorenson, 20, Social Science sophomore

- Bill Stewart, 19, Physical Education sophomore

- Gary Van Horn, 22, Crops senior

- Pete Bachino, San Luis Obispo insurance broker and team supporter